Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries

Link to full review

See our article in The Conversation

Photo by Antoine Plüss on Unsplash

Review question

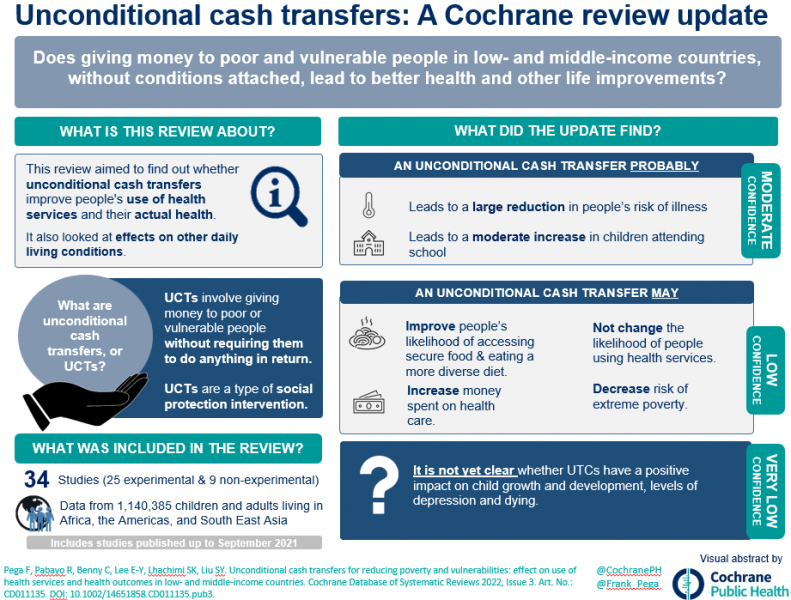

In some low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), governments and other organisations sometimes give money to poor or vulnerable people (for example, older people or orphans), without requiring them to do anything in particular to receive the money ('unconditional cash transfers'). In other programmes, people can only receive this money if they engage in required behaviours, such as using health services or sending their children to school ('conditional cash transfers'). This review aimed to find out whether receiving unconditional cash transfers would improve people's use of health services and their actual health, compared with not receiving an unconditional cash transfer, receiving a smaller unconditional amount or receiving a conditional cash transfer. It also aimed to assess the effects of unconditional cash transfers on daily living conditions that determine health and healthcare spending, such as attending school, owning livestock, having a job or being extremely poor.

Background

Unconditional cash transfers are a type of social protection intervention that addresses income. It is unknown whether unconditional cash transfers are more, less or equally effective as conditional transfers. We reviewed the evidence on the effect of unconditional cash transfers on health service use and health outcomes among children and adults in LMICs.

What did we find?

We included experimental and selected non‐experimental studies of unconditional cash transfers in people of all ages in LMICs. We included studies that compared people who received an unconditional cash transfer with those who did not receive a transfer. We looked for studies that examined health services use and health outcomes.

We found 34 studies (25 experimental and 9 non‐experimental ones) with 1,140,385 participants (45,538 children and 1,094,847 adults) and 50,095 households in Africa, the Americas and South‐East Asia. Governments or experimental researchers organised the unconditional cash transfer programmes. Most studies were funded by national governments or international organisations, or both.

Key results

We use the following terms to indicate our level of confidence in the evidence we found:

‐ 'probably' for evidence about which we are moderately confident;

‐ 'may' for evidence about which we have little confidence; and

‐ 'uncertain' for evidence about which we are not confident.

An unconditional cash transfer:

‐ may not have changed the likelihood of people having used any health service in the previous 1 to 12 months;

‐ probably led to a clinically meaningful, very large reduction in people's risk of having had any illness in the previous 2 weeks to 3 months;

‐ may have increased the likelihood of people having had secure access to food over the previous month;

‐ may have increased the average number of different food groups that people in the household consumed over the previous week;

‐ probably led to an important, moderate increase in the likelihood of children attending school;

‐ may have reduced people's risk of living in extreme poverty;

‐ may have increased the amount of money people spent on health care.

Despite several studies providing relevant evidence, the effects of unconditional cash transfers on the likelihood of children being stunted (having reduced growth and development) and on people's depression levels remain uncertain. No study estimated the effects of unconditional cash transfers on dying.

We are uncertain whether unconditional cash transfers impacted livestock ownership, participation in child labour, adult employment and parenting quality. The effects of unconditional transfers on differences in health were very uncertain. We did not identify any harms arising from unconditional cash transfers.

Three experimental studies reported evidence on the impact of an unconditional transfer compared with a conditional transfer on the likelihood of having used any health services, the likelihood of having had any illness or the average number of food groups consumed in the household. However, only one study provided evidence for each of these outcomes, and it was very uncertain for all three.

In general, where we had little or no confidence in the evidence, this was because people in the studies likely knew what 'treatment' they were getting (that is, a cash transfer or no cash transfer), and it was also likely that the researchers collecting information also knew which groups of people were recipients and which were not. Additionally, our confidence in the evidence was limited because in half of the studies, researchers were unable to collect follow‐up information from a considerable percentage of participants.

Conclusions

This body of evidence suggests that unconditional cash transfers may not impact health services use among children and adults in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Unconditional cash transfers probably or may improve:

‐ some health outcomes (such as the likelihood of having had any illness, the likelihood of having secure access to food, and diversity in one's diet);

‐ two social determinants of health (namely, the likelihood of attending school and living in extreme poverty);

‐ healthcare expenditure.

The evidence on the health effects of unconditional cash transfers compared with those of conditional transfers is uncertain.

How up to date is the evidence?

Current to September 2021.